Sometimes a GM’s job can seem overwhelming – after all there is so much to do. Generating stat blocks, preparing an adventure and designing a campaign world can quickly kill even the most organised GM’s free time…

Like all GMs, I find getting enough preparation time to keep ahead of the players in my Borderland of Adventure campaign a constant struggle. I previously talked about both tips to help prepare modules quicker and better and general prep tips for the busy GM, but sometimes you just need a plan. As people who know me will attest, I’m at my best when I have a plan of action – I hate wasting time. That’s why I’ve recently been developing and testing a new planning and preparation tool I’ve snappily called Three-Tier Design.

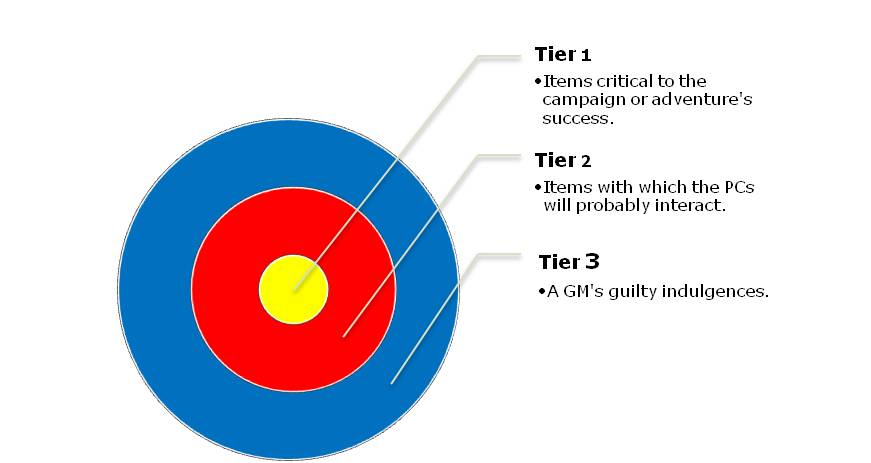

Three-Tier Design enables a GM to prioritise what is important for an upcoming session or adventure and to use his preparation time as effectively as possible. As its name suggests, Three-Tier Design comprises three distinct facets:

Tier 1

Tier one items are absolutely critical for the success of the session or adventure. They comprises stuff with which the PCs are virtually certain to interact. For example:

- Tier one items could include the villain, his guards, the main locations in a dungeon and a unique magic item or two.

- Other examples include the village inn (where adventurers normally stay), the clergy of the local temple who are available for spellcasting services and more.

- A GM should concentrate on preparing all tier one items before moving onto tier two.

Tier 2

Tier two items are those the PCs will probably encounter during an adventure or session. For example:

- Tier two items could include random encounters, minor NPCs in a town (perhaps skilled craftsmen, a couple of thieves and so on), world building elements such as interesting rumours and legends leading to alternate adventures, nearby locales of interest and more.

- Most GMs can improvise tier two items if necessary, but may need to note their details after the fact.

- A GM should concentrate on preparing all tier two items before moving onto tier three.

Tier 3

Tier three items are those the PCs are unlikely to encounter, but that the GM wants to design anyway. For example:

- Most GMs are inveterate world builders. Tier three items mainly comprises items that add depth to the campaign but which the PCs are unlikely to encounter directly.

- For example, the political machinations of a kingdom’s ruling elite could subtly affect the PCs, but the PCs are unlikely to ever come into contact with the nobles themselves.

- Other examples of tier three items could include detailed timelines of the campaign area, stat blocks for NPCs important to the kingdom (such as the king or a legendary wizard) the PCs will never meet and so on.

- Think of tier three items as a GM’s guilty indulgences.

Remember when planning your design time that new items will undoubtedly appear in the tiers as the campaign develops or the PCs’ adventures progress. That’s absolutely fine. It’s also absolutely fine to re-designate tasks from one tier to the other as the PCs’ goals or progress changes.

Help Your Fellow GMs

Do you have any more preparation tips for time-crunched GMs? If you do, share them in the comments below and help your fellow GMs prepare better games today!

I usually start one level up from here.

Before working on a scenario I identify — at a high level — what the PCs might expect to get out of the scenario, other scenarios it might link to (not necessarily how), and other major elements.

Then I drill down and identify elements within the scenario and their relationships.

Only after that do I start looking at the mechanics. I try very hard to not start on mechanics until after I know how the pieces fit together.

That’s a great way at looking at preparing to prepare! In my own campaign I often work several modules ahead – in a general sense – so the adventures link together in a more “organic” fashion. I also often have several possible lines of story advancement, and the PCs get to pick which one they pursue based on their actions. Having a “top down” view like the one you describe helps me achieve that!

It is useful, and doesn’t even necessarily take that much time.

I talk about it at some length in a series of blog posts at http://www.kjd-imc.org/hall-of-fame/setting-design/campaign-and-scenario-design/.

In fact, I even have an example. As part of this year’s A-Z Challenge I sketched out a few campaigns (a campaign is set of scenarios that together might achieve a significant goal; normally I plan each to run 3-5 character levels because less seems insignificant, more seems unending), then drilled down to explore a specific one, then finally down to the introductory adventure, The Keys of Heraka-at.

I still don’t have much by way of mechanics prepared for this adventure, but I am awfully close to being able to improvise it if I had to. I know the major areas of the scenario and roughly what is present, and while it would benefit from some detailed design (especially if others are to use it) I would be prepared to run it from here.

Thanks for posting up that link, Keith! I had a mooch about and found your node-based megadungeon post particularly interesting! I love megadungeons! 😉

I thought about linking the node-based megadungeon as well but thought two links per comment was enough 🙂

But yes, exactly the same techniques were used there. In fact, demonstrating the techniques was a major part of why I did in the first place.

I even included a bit of analysis on the time spent and something of an estimate of how long it would take (300 hours, +- 25%) to complete, and the volume (probably ~256 pages by the time supplementary material is included, if I had two pages per node).

Tier 3 constantly simmers in the back of my mind, and if I run out of time, or the players in my sandbox campaign world head somewhere unexpected, I can easily ad lib a four or five hour session of Tier 1 events simply because I KNOW the world. Of course, if I was using someone else’s prepared setting, I wouldn’t be able to do this. It also helps that I take notes while I run a session, so I can document/update whatever I was forced to ad lib… but I actually enjoy that process as well!

I take a lot of notes during sessions as well – both as a player and a GM. I’m lucky, I play once a week but still you can forget a lot between sessions. Having a handy set of notes is a godsend!

excellent advice 🙂 very strong article

Thanks very much – it’s the only way I survive as a GM!

Wow, this is just what I needed to see. I have a game to prep for Thursday and I’m actively prioritizing my tasks. Thank you for this timely release.

Great article! Using your diagram as a model, removing tier 3 from session prep should eliminate half of the task. Separating “session prep” from “world building” is a great way to reduce the time required to be ready for your next session. If you’re running a published module, there’s really no need for world building. Like you said, “guilty indulgences”.

Setting priorities is key, but so is being realistic about what your group will actually accomplish in a session. There’s no sense in writing out the entire inventory of a magic shop, if the characters don’t have the money anyway.

Creighton, were you an archer in a previous life?

I cannot lie–I have certainly arched in the past!