In my last post about Shadowed Keep on the Borderlands’s design I wanted to talk a bit about my general philosophy behind individual encounter design. But to set the scene, sadly I must first rant.

In my opinion, modules are getting harder. What I mean by this is that designers seem to be writing adventurers to challenge the super-optimised group – the kind of guys who tweak their characters to the nth degree. While there is absolutely nothing wrong with that style of play – in fact I do it myself on occasion – the problem is that writing to challenge the toughest, best prepared players inevitably rogers senseless the less prepared, casual, or god-forbidden, neophyte player who is just getting started with the hobby.

When I was on Living Greyhawk’s Circle of Six I witnessed a kind of bizarre, escalating arms race in which module designers and players each strove to outdo one another with the toughest legal builds. I like a challenge as next as the next player – there is nothing better than crushing the evil villain and saving the day – but similarly I don’t want every adventure or encounter I play to be balls to the wall, crazy dangerous.

As the “arm’s race” intensified, I got the impression that some modules were nothing more than a series of rather tough fights – the background, plot, environment, NPCs and everything else that makes a great module seemed to be more and more pushed to the periphery of the design process.

That was not going to be the case in Shadowed Keep on the Borderlands. Don’t get me wrong, there are challenging encounters in this adventure, but there are also very easy ones.

My Encounter Design Principles

So with that rant out of the way, here are the principles (or “the spine”) of my encounter design philosophy:

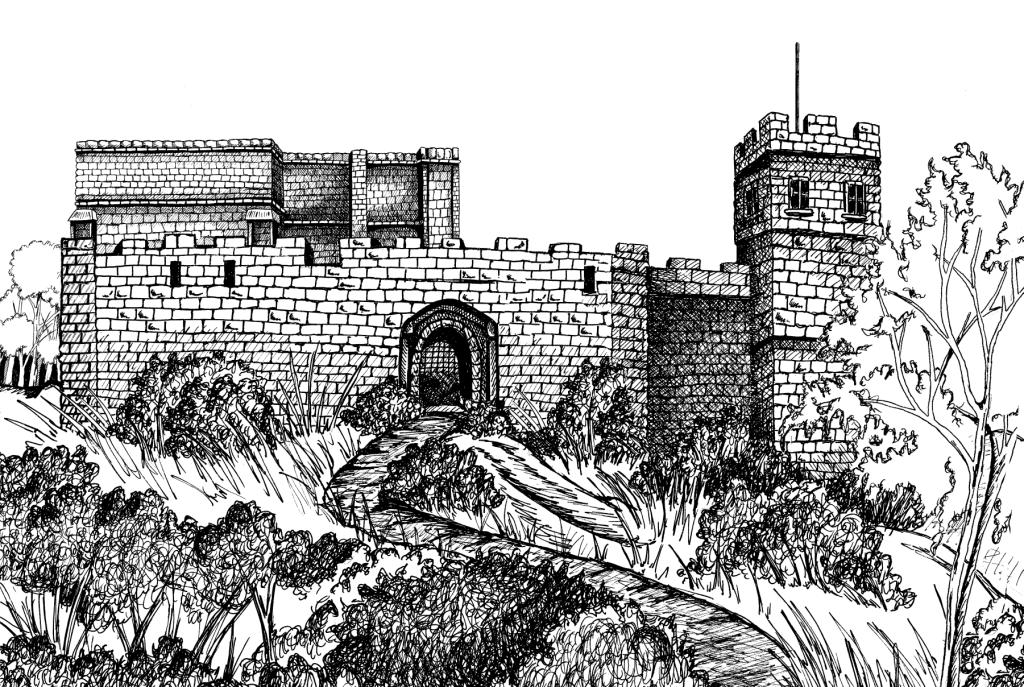

- Meaningful Choices: I loath railroading modules with the fiery passion of a thousands burning stars and I believe most players also feel that way. At almost every juncture, the players should have a choice about how they proceed. Do they try the tower or the donjon first? How do they get into the tower? Do they deal with the goblins or dare the undercrypts?

- Reward Clever Play: Players who pay attention, come up with clever ideas, remain observant and so on should be rewarded. Skill use should be rewarded. I tend to break skills down into two basic, very broad categories: combat (things like Stealth, Acrobatics) and knowledge (Appraise, Knowledge, Diplomacy etc.) Both sets of skills should be useful in the adventure. After all, if a rogue takes Appraise or a wizard takes Knowledge (engineering) and never gets to use them, that sucks. Part of the dungeon should only be findable if the PCs are paying attention, but this part should not be an essential part.

- Logically Consistent: Each encounter should be logically consistent with the history, background and current condition of the keep. What was the room once used for? What is it being used for now? Can the PCs make educated guesses based on the conditions, contents and decorations of the area?

- Danger: Obviously, there will be danger in the Shadowed Keep, but this danger should grow greater the further away from ground level (in either direction) the PCs venture. So, for example, the upper levels of the bandit’s tower and the upper level of the donjon are more dangerous that than the floor beneath.

- Avoid the 15-Minute Adventuring Day: I hate the 15-minute adventuring day. Such days normally come about because the challenges the PCs face are tough, forcing them to expend precious resources quickly. Encounters should generally be easier so the PCs can explore more areas without having to rest. This builds a sense of achievement and progression and leads to more “organic” forays where the PCs stop to rest after they have cleared a whole section rather than when they have run out of cure light wounds.

- Stuff for Different Classes and Races to Do: All characters cannot be equally engaged in every encounter all the time. That said, some classes (clerics, rogues, paladins etc.) are particularly suited toward certain kinds of activity. They should be given their time in the limelight. Similarly, are their places or environmental conditions that only Small characters can take advantage of?

- Environment: Fights don’t happen in featureless rooms. Furniture as well as unique features like rafters, chandeliers and so on can all be used by canny combatants to gain advantage. Include these where appropriate. Similarly, a decent amount of detail makes an encounter come alive. What do the tapestries depict? Is their graffiti on the walls? Are small, low-value treasures yet hidden within the keep that a good Perception check uncovers?

- Diplomacy: Not all encounters should end with a fight. Where appropriate, allow PCs to use cunning, duplicity and even diplomacy to “win.”

- Varied Opponents: Particularly tricky to achieve in the goblin lair, as goblin tribes tend to be made up of basic warrior types. Do the goblins pay mercenaries? Are they hosting emissaries from other tribes? Do different tribal warriors use different weapons or fighting styles?

- Be Easy to Run: This is huge; the best module in the world can be a complete disaster if it is hard to understand, prepare or run. Encounter text should do as much of the work for a GM as possible so that preparation is quick and simple.

This article is part of Dungeon Design Fortnight. Dungeon Design Fortnight celebrates Raging Swan Press’s upcoming release of GM’s Miscellany Dungeon Dressing – a huge 336-page tome dedicated to all aspects of dungeon design and dressing. I’m insanely proud of GM’s Miscellany Dungeon Dressing and I hope if you are thinking about designing dungeons you check it out.

I love you emphasis on eliminating the 15-minute adventuring day. It just doesn’t make sense. The guys in the next room aren’t going to sit around while you recover. Shifts are going to change.

I’ve heard the easy fights called “romps.” By having romps, you give the players more tactical choices. Do they take another bite at the apple? Or do they bunker down now and get it together before risking stirring a hornet’s nest with the next attack? Varying encounter difficulties makes scouting actually matter.

A little more of what I think about it: http://mindweaverpg.wordpress.com/2014/07/25/dungeon-mastery-romps/

Thanks for posting that link. I’ve never called them “romps” before but I often deliberately include encounters which the PCs can crush with amazing ease. It makes the players feel good and lets them flex their muscles. After all, if you have super hard encounters you should also have super easy ones too!

Your “rant” leads to my own. There has been a divorce between the Gamemaster and the player’s characters in campaign style play. Not only should encounters be designed with logic, so too should the adventuring party. Too often the tough encounter is a CR challenge instead of a crescendo of action furthering the players’ character’s story. Not only should the encounter make sense, it should make sense for these character’s to be there.

When you mention railroading, the evil cousin of railroading is the unnecessary roll or question proffered by Gamemasters everywhere. The king culprit of this is the overuse of the perception skill checks. If your party is mid level or higher with three or more players, go ahead and presume a certain level of success with those rolls because the chances are pretty good that one of your players will succeed at the DC20 perception. Too many times I see a gamemaster ask for a roll as an excuse to provide information to the players that they want the players to have.

The unnecessary question, is when the DM asks a question that creates a railroading situation. Don’t ask right or left if you only have the right prepared, just describe the path to the right. It only feels like railroading if you give them a choice and then argue against or resist their choice. If you put the Deck of Many Things in the Encounter, MANY THINGS CAN OCCUR! LOL

You make a good point. I quite like the passive Perception check in 5e. Basically, if a PC has a perception check of +11 (for example) assume they make a DC 21 without bothering to roll. Nice, tidy and quick. I’d also strongly consider doing the same with Knowledge checks.

I agree about the knowledge check. Many times with my Wednesday crew, I try to use the knowledge skills of the PC’s to to reveal key info in ways that make that PC appear smarter. The nice side effect from this approach is that many times the players realize they are probably the more knowledgeable authority on a subject and don’t waste a lot of time trying to find an answer from outside their group without my having to “railroad” them in a particular direction.

I have a different take on D20 rolls the players make at odd times.

If the only time you ask for a check (even if you are non-specific as to what you are comparing it to), then that immediately provides intelligence to the players that there is a threat or secret nearby.

Randomly asking for rolls, taking results, and not specifying what your purpose is often creates suspense in places there *could* be a threat or enemy, but isn’t, so when you ask for the real roll, they don’t feel it is any different (if not much happened before, they may feel nothing will again incorrectly and if they think every corner could contain a threat, they play generally more cautiously which is kind of the spirit of old school – cautious or dead.

I do agree that sandbox style is much preferable to the railroad. I find modules written as if they were stories or plays (3-act structure, or a set narrative of scenes and outcomes) just totally kills player agency. Instead, you should design by putting some actors in your area, knowing their motivations and resources, then imagining their plans from their available information. Let player decisions plus the NPC’s choices logically and naturally lead to the encounters and then look again at how that encounter impacts other NPCs with plans (and the party would then likely be doing the same analysis). It’s more thinky, but it gives the players a ton of agency in deciding how they direct their efforts.

Creighton,

Some sound design principals.

One module that made the 15-minute day impossible or at least super hard was one of the Slavers series where the baddies were smart, had patrols, knew to warn was their first duty, and once you kicked up the anthill (not literal, not thinking of the aspis), more and more forces would try to converge on you. You either hid, pulled back, or were darn careful in the first place (and quiet).

I wanted to comment on the escalation thing and ‘design for optimized PCs’ (that could also include otpimized parties with excellent synergy vs just individual optimizations)… it’s a design failing.

Now, if you run a lot of characters that have sub-par stats, you wil statistically find that they die more often and don’t make higher levels vs. those with higher stats, all other things being equal. So one can almost expect higher level PCs to be optimized by natural selection (parties too). That said, for an intro adventure with newbie characters (even if not players), that’s out of place.

One thing I’ve always thought was important when I made my notes for an encounter was:

Standard foe description

Notes on how to weaken the encounter if the players are taking a kicking before this (assuming it was bad luck vs bad choices!)

Notes on how to strengthen the encounter if the players are running amok

It doesn’t take much space, but having the choice in each encounter lets you think about if you need, as a DM, to modify things on the fly to ease the threat or increase it. And having a bit of pre-game thought about how is useful too.

I do think enemies get surprised. Sometimes their morale breaks because they had a bad day or they feel like there is a greater threat than the PCs actually represent. Sometimes enemies make non-optimized choices (esp the dumber ones). Sometimes an enemy has rolled less than 5 on 4 consecutive attacks and may decide his foe is much better than he thought or that he personally is having a terrible day and it is time to retire.

My enemies surrender too and that places a burden on the party that is fun to watch. Some will offer up something for their freedom (knowledge, loot). Some might even offer to change sides to work for the tougher team on the block. Not every encounter, even if there is a fight, needs to be to-the-death.

I like it when enemies surrender. As you say, it change the dynamic of the situation. Prisoners make sneaking about, swift tactical manoeuvres and the like very tricky. Dealing with them can spawn some great roleplaying moments, which is often a nice change from incessant combat.