I’ve written a fair amount about dungeon design over the last few years. Recently, I came to a startling realisation!

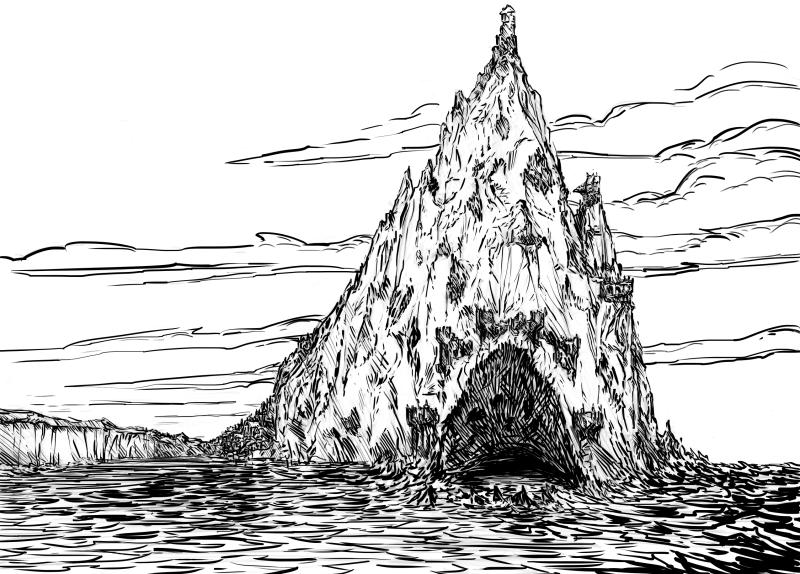

Good dungeons need many things: a purpose for existing, an evocative name, an ecology that actually (vaguely) works, interesting features, a decent range of dungeon dressing and more. What they also need, however, is a decent swath of wilderness in which to lurk.

Consider these examples:

- The castle in I7 Ravenloft is surrounded by wilderness rich in minor adventuring sites.

- The ruined monastery and the dungeons below in B5 Horror on the Hill (an overlooked classic) can only be reached after a gruelling trek through the monster-infested wilderness.

- The Tower of Heavens (from UK5 When a Star Falls which is another overlooked classic) stands at the centre of a great swath of hills and mountains.

- Sakatha’s tomb hosts the climax of I2 Tomb of the Lizard King, one of my all-time favourite modules. It squats amid a noisome swamp, and just reaching the place is an achievement.

Would any of them have been as good adventures if the wilderness portions were removed? Hell, no.

That said, some modules are undeniably marvellous even without a well detailed surrounding wilderness (but would have been much better with one added). For example,

- The Moathouse from T1 The Village of Hommlett is perhaps one of the greatest—if not the greatest—low-level dungeon crawl ever written. (The village is awesome as well). Sure, it’s not fancy and it’s not sophisticated, but it’s brilliant nonetheless. How much better could it have been, though, if Gary had taken time to flesh out the surrounding countryside?

- The Caves of Chaos from B2 The Keep on the Borderland is a classic adventure site. Literally millions of heroic adventurers have fought the foul creatures dwelling therein. Sure, the area around the caves does receive a little bit of design attention in the module, but it could have been so much more.

What’s So Great About the Wilderness, Anyway?

Adding an area of surrounding wilderness to a dungeon does several things:

- It creates separation (or perhaps a buffer) from civilisation. Often this gives the storylines of the dungeon more realism; after all if the orc tribe lives next to the town why hasn’t war come to the region? Similarly, if a ruined temple is to remain unexplored (and unlooted) it’s much better located far away from prying eyes.

- It creates different challenges. Rangers, druids and the like often shine in the wilderness, but sometimes struggle to bring all their abilities to play in a dungeon. Providing an area of wilderness gives those characters somewhere to be in the spotlight. It also enables a GM to use different kinds of monsters—monsters that probably wouldn’t make sense in the dungeon—and different kinds of challenges.

- It creates a transition zone. Often jumping immediately from a tavern’s comfy common room into a deadly adventure can be jarring and disconcerting. A wilderness area provides an environment in which the players can “warm up” to the adventure.

- It creates somewhere to tell the story. If the dungeon is stuffed full of orcs, undead or whatever, a surrounding wilderness gives the GM somewhere to tell a little bit more about the story. If bandits lair in the ruined castle, the party might find the nearby roads mysteriously empty of traffic or merchants only travelling under heavy guard. They may even find slain merchants, abandoned wagons and so on. Such details build flavour and may even give the party important clues about what lies ahead.

- It creates the possibility of sanctuary. Even the harshest wilderness has pockets of safety. Canny PCs can retreat to these areas—hidden caves, fortified homesteads of brave settlers and so on—to rest and recuperate without having to retreat all the way back to town. Sometimes, the PCs may even be able to get significant help at these sanctuaries.

Putting it into Practice?

All this has got me thinking about a module I wrote several years ago: The Shadowed Keep on the Borderlands. I designed it as a homage to the Moathouse in T1 and to date it’s been rather well received. (It’s also Raging Swan Press’s best selling product).

However, I’m beginning to think the module would have been much better if it also had a richly detailed surrounding wilderness area. (It could also do with a nearby town for the PCs to retreat to, and some expanded cavern levels, but that’s the subject of another post!)

What Do You Think?

Do you agree or am I talking rubbish? Let me know in the comments below.

I6 Ravenloft 😉

Other than that, very much agree. I do think though, that adding much wilderness and a town and more to Shadowed Keep will turn it into a sandbox mini-setting. Which is great, but a whole different type of adventure type than now.

I agree wholeheartedly. Many times in my career as a DM, have I found It important, yes important, to add wilderness to a module or storyline.

Would the venture to Lonely Mountain been half as exciting if there was no Kirkwood. I say, nay. It added so much. Gave characters to the story moments to shine, added comic relief at times, assisted with the overall mood and finally, on point to the central overall plot.

Wilderness is so easy to manipulate and modify to any story. Most people limit themselves to a singular style of thinking when it comes to wilderness. When in reality, wilderness is all you make it, ever evolving and mood setting.

I cannot accept a module as complete without thus kind of flair. It’s like having the best entree at a restraint but eating leaving off appetizers and beverages.

Err. Typo Mirkwood, as it were.

I would suggest a Lego approach to this which would fit in with how much of your content is organised:

– keep the current adventure as is

– make one of more village backdrops for towns that are relatively near, each with their own adventure hooks

– make a wilderness setting containing containing the keep and the villages (with concise descriptions / references to each), and some adventure hooks for having ‘fun’ in the wilderness

– make new adventures that take place below the keep, such as:

— Deep Shadows In The Borderlands

— Lost City Below The Borderlands

— Shady Deeds Under The Borderlands

Frits’ suggestion to “branch off” new adventures from your core adventures (i.e. Deep Shadows in the Borderlands) is excellent! Creighton, your flagship adventure modules seem to get the occasional “Collector’s Edition” upgrades (making awesome modules even more awesome) … and this branching-off addendum/pathway might be an interesting variant for you to pursue.

Yes, I liked his idea as well! In fact, today, I made some general notes about what I’d like to add to the Shadowed Keep. It was a fun list, and I’m hoping to have more time to flesh out my notes.

I couldn’t agree more. one of my more favorite modules is Hollow’s last hope. PFRPG. Fully the first half of the adventure is spent on a scavenger hunt through the surrounding forests. Each piece of the puzzle is its own encounter, plus there is numerous random encounters already done up, that fit nicely with the overall story.

I always figured that the Shadowed Keep on the Borderlands should go somewhere on the Lonely Coast.

Long, long ago (25+ years ago), when I began designing my wilderness for my early D&D campaign I combined the Keep on the Borderlands, In Search of the Unknown, & The Village of Hommlett/Moathouse into the same general area, along with a couple of my own mini-encounters & used an expanded wilderness map from the Keep on the Borderlands with expanded rumor/encounter lists from that product. It worked out incredibly well. Ah, the fond memories…

Excellent advice and very true. If such places were not remote and surrounded by dangers and overgrowth (and that’s why they are likely remote, because otherwise people would just stroll up to them and clean them out, they aren’t malls in urban population centers after all, they are dungeons and ruins) then they wouldn’t be really dangerous.

Places that are easy to reach are subject to being easily cleaned out and domesticated by the local authorities and militias and populations. The more dangerous and/or the deeper the gauntlet to run in order to reach the ruins the more unlikely anyone will have cleared the area and the more likely the central attraction will be far more lethal.

The transition zone though need not be only a geographic and physical transition zone, but very much like in the old Tomb Raider games a transition zone between “ordinary mundane reality” and the “competing presence of powerful magics, supernatural miracles, and uncanny preternatural beings.” You transition not just from place to place but from Reality Ruleset or Environment to an entirely different Reality Ruleset.

One is very unlikely to see a dragon in a city or settled habitat in most settings and games, or wraiths or barrow wights or manticores milling among men because men don’t build settlements when such creatures are around, or such environmental conditions exist. They either build elsewhere or kill off such creatures. Same thing with truly dangerous magics and supernatural entities. The vast majority of people are uncomfortable and wary in the presence of such things, or everyone would be a Hero and every monster already tamed.

The wilderness is, on the other hand, uncomfortable and rebels against being settled and domesticated. It has a very different view of Reality. So do Frontiers. That is why so many powerful adventures and dungeons and Quests and ruins inhabit both areas.

Good article and observations.

I2 is also my favorite dungeon delve and the wilderness definitely adds to the tension and makes the fight much more personal. I’m sad I threw Dayan from Halls of Undermountain against my current party or I’d throw Sakatha against them sooner. Two many vampires in a row isn’t fun.

You could always wait a bit, lull them into a false sense of security and then strike!

It’s definitely a thought-provoking article. I wonder about this all the time. While researching for my own campaign world, I looked at distances, wilderness vs. civilisation, and size of forces quite a bit. The Dales in Forgotten Realms are huge, more like vales. Within each FR Dale there could be many actual dales. So, then I turned my attention to the Yorkshire Dales and decided I would base mine on those. It turned out to be my own Shire, in the end. Small settlements no bigger than medieval towns at their largest, with very little standing troops, heavy reliance on militia forces. So, even though the areas of wilderness are relatively close to settled regions, the military might of those regions aren’t great enough to warrant sending its men into dangerous areas without a huge threat. A swift and tactical strike could disable a human town. So, adventurers willing to brave the wilderness to face the enemy is welcome so the non-classed militia masses can stay in the safety of the settlement.

There are many things to consider when determining the reason for why a group of professional soldiers would shy away from a region. Superstition, size of the forces in question (a small standing army would likely remain behind to protect its citizens rather than venture off and risk leaving their home unprotected), alliances (are the nearby settlements loosely organized (mostly just relying on themselves to solve most problems) or are they a tightly knit network under the protection of a local lord or king (or high king)? Most people would happily hire mercenaries to handle a situation. If the hired forces fail, the blame falls on them. If they succeed, so much the better. Plus, in game terms, classes are very unique. Not many folks achieve levels. PCs are special. 0-level folks are not likely to be very adventurous, they are too concerned with their daily lives. After all, D&D largely deals with agrarian societies. If the farmers get up and leave to slay the dragon, and they die, the kingdom will suffer worse than if the dragon was simply left to steal a few sheep and eat a few villagers (not to mention the aftermath of pissing off the dragon). Take one of my favourite movies, ‘Dragonslayer.’ An elected group of peasants go in search of a powerful wizard to deal with a dragon that they themselves cannot handle.

That’s the double-edged sword of being an adventurer. An armoured warrior walking into town is a rare spectacle. Enough so that a superstitious group might either see him as a boon in their time of need, or attach their troubles to the hapless mercenary, even if he is not connected in any way to their problem. ‘Must be a king.’ ‘Why?’ ‘He hasn’t got crap all over ‘im.’ Besides, most people are not willing to stand up and do anything in a crisis. Take the number of Youtube videos featuring a crowd of people recording a homeless guy getting beat up by a thug. No one does a thing.

Again, this article is a topic I think about constantly. How to retain a sense of realism in a fantasy setting. Specifically, how much buffer is enough to warrant the involvement of/need for adventurers? The simple fact that a society’s livelihood relies solely on the success of their farming and husbandry can both spur peasants into taking action and likewise keep them paralyzed lest they risk their crops and livestock, not to mention leaving the routines and lives they are comfortable with.

How big would an enemy force have to be, and how far away, before action would be taken? Take all the Romance stories from England. It’s small landmass means there isn’t much space for wilderness, and yet there still manages to be some spooky wood, cave, or moor that no one wants to enter. A king might be unable to rally support if his neighbors do not like him, thus necessitating the need for mercenary adventurers. And most folks aren’t willing to act until death is literally knocking at their door. Out of sight, out of mind, after all.

Thank you, Creighton. This is a great article dealing with a topic I am constantly thinking about.